In response to a call for content for a book titled Hack(ing) School(ing), I wrote an article on how we should replace middle- and high-school history content standards with helping students to develop curatorial skills. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the topic. Check out the post at my more academic blog, The Clutter Museum.

Between education and curation

(cross-posted from The Clutter Museum)

There’s been a ton of talk over the past year about how participating in social media—whether through blogging, social bookmarking, Twitter, Flickr, or whatever—can be a form of curatorial practice.

And I totally get the appeal of that particular metaphor. In fact, I understand that some people mean to use it in a very literal way, in the sense that they see themselves as imposing a welcome order or useful narrative on a very unwieldy collection of internet artifacts. I’ve seen some people I think are absolutely brilliant using the term this way.

Those who know me well know I don’t roll out my Ph.D. lightly. But as an (OK, adjunct) professor of museum studies and soon-to-be assistant professor of public history, I have to call bullshit on this one. As a lover of metaphor and as a poet who embraces all the possibilities of metaphor, I completely expect commenters to tell me to loosen up in this case. In fact, I suspect I’ll come across as a snob. But really, this distinction—what is curating, what very much isn’t—matters tremendously.

Educators with some facility in social media have become particularly fond of the term. But education isn’t curating. Curating isn’t education. In fact, in many museums, curators and educators are, alas, at odds with one another. Traditionally, curators have developed a depth of expertise in a content area over years of study, while educators tend—and yes, I know I’m generalizing here—to be younger folks with less education and experience. Education positions have a ton of turnover, a ton of burnout; curatorial positions come with more prestige and a sense of ownership of a position, sort of like tenure. Curators have at least a master’s degree and frequently a Ph.D. Educators have undergraduate degrees and increasingly, in this era of incredible competition for jobs, master’s degrees.

I don’t mean to imply that curators are above the fray, that they hold themselves at arm’s length from education. But their function is different. Curation is not a process of choosing the best resources to help other people learn. It’s much, much more, and to suggest that social bookmarking, sharing links via Twitter, or using an internet platform’s algorithm to help you determine which songs belong on your internet radio station is curation is ridiculous. Differentiating among things you like and dislike, or resources that you think are good or bad, and then sharing those opinions with people as a collection of internet or educational resources, is not curation.

When people talk about “curating” via social media, they’re really talking about filtering, and curators do so much more than filter. You can’t, I’m afraid to inform Robert Scoble, just “click to curate.” In fact, the absence of talented curators makes a given educational context degenerate, in newcurator’s most excellent formulation, to reality television.

Educators also do more than filter. They translate the curator’s research and expertise into small bites digestible by the general public or schoolchildren. This is a talent unto itself, and—as a former museum educator and exhibition developer—it’s not easy to develop because informal education diverges so spectacularly from what we’re all taught is supposed to happen in formal educational settings.

The conflation of a combination of sharing, digital resource connoisseurship, and online teaching and learning with a form of curation not only devalues the actual practice of curation—and by extension the time, effort, and passion it takes to develop sufficient expertise to become a curator—but also obscures the skills we hone as we navigate sharing on the social web.

We need a new term for folks who are developing (or who have already developed) the depth of expertise that marks curatorial work, but who also practice the distinctive forms of teaching and learning engendered by the social web. It’s not exactly edupunk, and it’s not museopunk.

In my mind, the people—and particularly academics—who occupy this space practice Keats’s “negative capability”: they are “capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.” By this I mean they get the tension—apparent to anyone who has planned a college course or an exhibition—between helping students or visitors develop content expertise and giving them opportunities to think critically and creatively. Doing both of these things simultaneously—cultivating expertise and promoting real intellectual development and discernment—is incredibly difficult to do from a lectern. The social web, like a provocatively interactive museum exhibition, offers new possibilities for this kind of participation in, and service to, the world.

California Academy of Sciences botanical curator Alice Eastwood standing on the scarp of the San Andreas Fault, 1906. Eastwood was both a curator and an educator.

California Academy of Sciences botanical curator Alice Eastwood standing on the scarp of the San Andreas Fault, 1906. Eastwood was both a curator and an educator.What we call that exciting—and dare I say disruptive?— role is open to discussion and debate. Kindly leave your witty neologisms in the comments.

Update: Just saw this article on the new curators in the New York Times, which in some ways undermines my argument and in other ways reinforces that curating is its own special skill set. An excerpt:

It is also a group plugged in to all areas of museum life. They don’t simply organize exhibitions, they also have a hand in fund-raising and public relations, catalog production and installation. “The old-fashioned notion of a curator was that of a connoisseur who made discoveries and attributions,” said Scott Rothkopf, 33, who is the latest full-time curator to join the Whitney Museum of American Art’s team. “A lot of that work has already been done. The younger generation is trained to think differently, to think more about ideas.”

Professional development in museums

Note: This is a revision of an earlier version of this post.

As an adjunct professor in John F. Kennedy University’s graduate program in museum studies, professional development is frequently at the front of my mind.

By “professional development,” I mean helping students and emerging museum professionals become more thoughtful museum thinkers and makers. I’m talking about learning to think more critically and creatively about both one’s niche within the museum world and the larger system of the museum (or museums). Much of the writing on museum theory and practice can contribute, of course, to professional development, but no number of how-to articles or books contextualizing contemporary museum exhibitions and programming is sufficient in itself.

The difference between learning how to do something in a museum context and developing oneself professionally within the museum field is frequently vast. It’s the difference between reading an article on how to grow tomatoes (and subsequently planting tomatoes) and reading a book like Food Not Lawns and planning a suburban or urban garden that recycles resources via a system of ponds, swales, compost heaps, and seed preservation.

The most effective professional development takes place within systems and networks. In my experience, the best professional development frequently happens spontaneously, in the form of “a learning community assembling itself on the fly.” I borrow this phrase from Gardner Campbell’s talk for the University Continuing Education Association’s 2009 conference. Campbell emphasized the importance of catching a thought and pushing it along via conversations and networks–in Gardner’s example, by tweeting and retweeting on Twitter. “It’s a very playful way to interact,” Campbell said. “It’s purposeful, too. And you can’t control it. You shouldn’t try to shape it too narrowly. There are other things we can do for that. The term paper is not going away. The research project is not going away. . . Pushing the thought along actually lends a kind of vividness, a kind of energy, a sense of shared purpose to whatever you’re doing in a learning situation. It’s quite remarkable.”

I’m a bit embarrassed that I haven’t directly addressed this topic in previously in a blog post. I spend 40+ hours a week in the University of California, Davis, teaching center, trying to get faculty to be, in my mentor Jon Wagner’s phrase, more thoughtful about teaching undergraduates. I also help graduate students be more effective instructors, and I’ve founded a professional development consultancy. In short: I “do” professional development. I also teach museum studies graduate students, inculcating them into the field via an introductory history and theory seminar and by overseeing their master’s theses. I have quite a bit of experience and expertise in what works and what doesn’t in professional development in academic and nonprofit contexts; I’ve just never synthesized those experiences in writing.

In this post, I’m going to look at some best practices in professional development as well as look at the learning communities that are sprouting organically or intentionally from various social media platforms. By looking at these phenomena, I’m confident we can plot a more deliberate course–and yet one customized for each individual–for the professional development of our students, our colleagues, and ourselves.

Seven best practices in professional development

1. Professional development must be anchored to learning objectives. Professional development is not about “training” or just being polished and well-informed. A professional within the museum field is someone who can demonstrate knowledge of the field, yes, but also someone who is an experienced and open-minded learner, someone who

- cultivates broad networks within and across institutions,

- communicates well verbally or in writing,

- is a savvy and generous collaborator,

- exhibits an extraordinary degree of resourcefulness, and

- balances critical and creative thinking.

The challenge comes when we try to specify the desired outcomes of these objectives, when we translate them into behavioral objectives on a professional development plan. These behavioral objectives will vary depending on the individual’s interests, institutional needs, and the size, focus, and scope of the museum.

For example, specific and measurable learning objectives in a year-long professional development plan as stated by an emerging museum professional who is in education at a small textiles museum but who has an interest in moving into curation at some point in the future might include:

- Determine which research emphases textiles are in demand (either at her museum or in the field more broadly), pick one, and read at least six books and exhibition catalogs, as well as multiple recent journal articles, on those textiles and the cultures producing them.

- Contact relevant journal editors and volunteer to write reviews of recent books of interest.

- Establish a collegial, and preferably a mentoring, relationship with an expert textile cleaner or restorer.

- Start a blog that educates laypeople about specific textiles’ origins, significance, and/or conservation. Curate a resource page of links to, and a bibliography of, materials on the subject.

- Attend a museum conference that textiles specialists are likely to attend.

- Join relevant associations or research groups in the museum field or textile industry.

- Research undergraduate courses and/or graduate programs that offer hands-on experience with textiles.

2. Conversations are essential to professional development. If you’re working at a small museum, you may find yourself without many people to talk to about what you’re working on. So, for example, if you’re a museum educator who is looking to find more thoughtful methods to interpret a new exhibition, you should be talking to someone who has interpreted an exhibit in a way that intrigued or inspired you, and engaging with the teachers who will be bringing their students to the museum. These aren’t just sound practices in exhibition interpretation; they’re opportunities for you to learn more about what’s going on in other museums and what teachers feel their students aren’t able to get from a traditional classroom experience.

3. Effective professional development stimulates more creative and critical thinking. By critical thinking, I mean analytical thinking, the ability to break down a scenario or information into its constituent parts and immerse oneself in studying and critiquing the details. By creative thinking, I mean synthesizing information from diverse sources to create something new and interesting. That means, of course, that the best professional development opportunities offer specific case studies for participants to study and address as well as particular problems for them to solve.

4. Professional development allows individuals to create their own networks by introducing them to network nodes in their areas of interest. A node is someone who is well-connected in their field or across disciplines or genres of museum participation. We all know people like this in our own workplaces, the people with 500 Facebook friends or 2,000 authentic followers on Twitter. These nodes draw on the expertise of their networks with a simple query via Twitter, blog, or e-mail, and connect individuals with one another.

5. The best professional development has both online and face-to-face components. Professional development is local and national and international. Museums should pool resources and collaborate with other institutions in their region for the mutual improvement of their staff members. We see this beginning to happen with the Balboa Park Cultural Partnership’s formation of the Balboa Park Learning Institute. Here’s a description of the project from the IMLS website:

The Balboa Park Cultural Partnership, a collaborative organization comprising 24 diverse museums and cultural institutions in San Diego, will establish the Balboa Park Learning Institute (BPLI). Over the three year project period, BPLI will design a professional development program targeted to the 2,500 professional staff members, 500 trustees, and 7,000 volunteer staff members in the park’s museums. As BPLI expands, the classes will be made available to museum colleagues and volunteers outside the park. BPLI will develop and present 66 workshops to build knowledge and skills in core museum competencies. Professional evaluation and assessment throughout the

project will prioritize learning needs and refine program delivery techniques. Three symposia will also be offered, bringing together

staff and volunteers from park institutions and beyond to learn about and discuss best practices in museum management and leadership.

Workshops and symposia should emphasize not just content coverage but conversations and connection. These connections and conversations can continue in an online forum, either one specifically set up to further the conversations started at the specific event or a more common tool like Twitter or Flickr.

The platform you choose is important. For example, in my experience, people aren’t going to contribute to a wiki set up for a one-time event, but they might visit a site that aggregates filtered content from their individual Twitter streams or blog feeds. (Select and promote a hashtag (e.g. #aam09) that people can use in their tweets or a tag to use in Flickr and on blogs.) If you have an ongoing project, a group blog or wiki (see, for example, the Smithsonian’s Web and New Media Strategy wiki) might be a better place for everyone to contribute. Or, you might partner with a forum like Museum Professionals to expand the learning that takes place at your professional development events beyond your institution(s) and encourage your participants to engage with professionals from outside your institution.

6. Professional development should be viral. In addition to finding a space for conversations to take place via forums, photo streams, or microblogging, arange in advance with museum blogs to have your staff write about your professional development event in guest posts on others’ blogs. In this way diverse but informed voices can join the conversation.

Similarly, if you missed a conference–say, the American Association of Museums conference or Museums and the Web–be sure to search Twitter for the appropriate hashtag, for example the 2009 AAM hashtag, #aam09. In such conference microblogging streams, you’ll find a wealth of information about what’s going on at the conference, links to conference content, and discussions taking place among attendees–which you should feel free to join in, even if you aren’t at the conference. Many times I’ve been at conferences where the conversations were enriched by people “attending” remotely via Twitter.

7. The best professional development makes space for evaluation. Let’s look back at our hypothetical emerging museum textiles professional in #1. How shall we go about evaluating the professional’s success in meeting her objectives? Measuring collegiality, for example, is difficult. This is a huge topic to address here, but you can expect to see it addressed in a future log post or in one of my museum professional development newsletters.

Ready for more professional development recommendations? Part II of this post, which will focus on social media, is coming soon.

Millennials in the museum: an educational dilemma

Although I teach in a museum studies graduate program (and wish I could do it full-time), my primary job is to help faculty become more thoughtful about teaching undergraduates at the University of California, Davis. Since I began working in the university’s Teaching Resources Center, faculty have come to me for assistance with myriad issues, but there are three that arise more frequently than others:

- They are teaching very large (200-900 student) classes.

- They feel compelled to cover large amounts of material.

- Their students can’t think analytically–or write.

The first and third of these quandaries are generational ones in that in the U.S. we are educating students in an era of reduced resources, higher enrollments, and high-stakes testing in K-12. The second quandary relates intimately to the first and third.

The problem of coverage, what I have heard termed “the tyranny of content,” has of course long plagued curators and exhibition developers as well as professors. In museums it takes many forms: a desire to exhibit all the varieties of one object (e.g. butter churns, to borrow an example from Dan Spock) or to cover an immense amount of material and history in too small a hall (e.g. the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s African Voices exhibition), for example.

Museums have also long had to deal with large numbers–sometimes crushing numbers–of visitors to new, blockbuster, or otherwise favored exhibitions. How to serve so many people while still giving each visitor a sense that she has had a personalized interaction with the museum content is one of the great quandaries of museum education, and we’re barely scratching the surface of this problem with some tentative experimentation with digital and/or mobile devices.

The new generation of young adults, however, presents a particular challenge to museum educators, exhibition developers, and docents. If they attended a public university in the U.S., and especially in California, these “Gen Y” “Millennials” are likely to have been a victim of what I call the factory farming of students: large lecture halls crammed with students, multiple-choice tests, and a long series of general education courses that represent to them not opportunities to explore new disciplines, but rather a series of boxes to be checked off: the writing requirement, the diversity requirement, the quantitative thinking requirement, etc. In addition, these college students and graduates came of age under No Child Left Behind, a regime of high-stakes testing that led school districts to “teach to the test” rather than engage in the student-centered learning that imbues young people with curiosity, gives them the intellectual tools and cultural literacy they need for interpreting and analyzing the world, and ensures a desire for lifelong learning. Many of these young people are thus victims of large-scale, depersonalized educational systems. Trained to memorize and regurgitate instead of interpret and create, they are not equipped to engage with museum content–and worse, they may not even be aware of their predicament.

Clearly, this generation provides an opportunity for–or, rather, is in desperate need of–visitor studies that examine how trends in our K-12 and university systems affect museumgoers’ understanding of material culture, art, hands-on science exhibits, and natural history objects. What new kinds of interpretation will we need to develop? How can we teach interpretive skills to those in galleries as well as convey content?

Based on my own experiences in the Gen Y classroom, my observation of others’ classes, and my consultations with faculty, I offer here some tentative suggestions for meeting the needs of Gen Y learners in the museum.

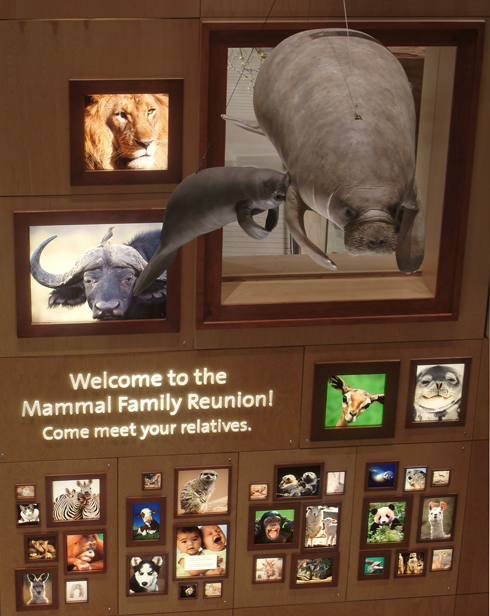

Provide strong orientation. By this I mean museums need to strike a balance between free-choice learning and making learning objectives painfully explicit. How this might look will vary by institution, but one place to start is with a strong framing device. One exhibition that accomplishes this well is the new mammal hall at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. There is no clear pathway through the exhibit hall, and it’s easy for the dramatically lit trophy-quality mounts and evocative soundtrack to overwhelm the visitor with their pure spectacle. However, the museum has framed the exhibition in an orientation gallery, using this conceit:

photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

Visitors are welcomed to the Mammal Family Reunion and learn that mammals can be identified because they all share three basic traits: they have hair or fur, they possess specialized middle ear bones, and they produce milk for their young. Elsewhere in the exhibition, visitors learn more about mammals’ diverse environmental niches and adaptations, but the framing device is that all of these animals, despite their tremendous diversity, are from the same “family” (more precisely, the same class within the phylum chordata). Certainly there are some of you saying, “Really? That’s all people are going to take away from this exhibit? That mammals are hairy, produce milk, and have something in their ears?” To which I say:

- Millennials have learned to memorize and retain, at least temporarily, facts about a subject. Learning (or, in the case of college-educated millennials, re-learning) three things about mammals is an excellent starting point for them.

- Millennials’ science education has suffered in K-12 as a result of NCLB’s emphasis on math and reading comprehension. Drop them in a place as large as the NMNH and they’re going to feel overwhelmed. Give them a flash card’s worth of information to begin with, and they’ll feel comfortable.

- This is only orientation information, a short list of objectives they can carry with them as they wander around the exhibition and apply these facts or principles to what they’re seeing.

Ideally, as the visitor walks through the mammal hall, she would be learning concepts that build upon these basics. For example, mammals all have fur or hair, but they have differing amounts of it. A jackrabbit and a sea otter have dramatically different densities of fur because they have adapted to living in very different environments. Although they descend from a common ancestor, these animals evolved in ways that allowed them to occupy, and even thrive in, a niche.

Help visitors develop analytical frameworks and interpretive skills. We see a bit of this in the example above. Visitors learn three basic facts, and then begin to make observations on their own about each fact–e.g. that mammals’ fur density differs by species. Next the visitor should be prompted to puzzle through why the fur differs. And then comes the big lesson: What are humans doing to change the environments in which these animals live? What happens when an animal evolves over tens or hundreds of thousands of years to occupy a niche that is decimated by humans in a matter of years? What are humans’ responsibilities to endangered mammals? Why might humans be more amenable to protecting mammals (AKA “charismatic megafauna”) than they are other species, and what are the advantages and liabilities of this approach to conservation? Labels, podcasts, hands-on activities, docents/explainers, and visual organizers all can contribute to this learning.

Customize streams of content. Provide interpretive tours organized around visitor interests instead of gallery space. Offer audio tours created by a variety of experts or amateur enthusiasts, including “guerrilla” audio tours. Examples from our mammal hall might be an evolution-focused podcast, a conservation-focused activity book or handout for children, or ways for visitors to send themselves the URLs of content related to the exhibition areas in which they’re most interested–e.g. polar mammals or desert creatures.

Provide content in multiple formats. The streams of content you provide must be accessible in several formats. This might mean visitors can generate e-mail messages to themselves–perhaps a series of autoresponders–to learn more post-visit, send to their mobile phone or PDA the snippets of code they need to embed customized media in their blogs or Facebook news streams, or pick up topic-specific paper handouts upon exiting the exhibition.

Offer opportunities for collaboration. Hands-on exhibitions sometimes call for cooperation among visitors, but opportunities for collaboration are rare–and it is a skill that Millennials may not have had the occasion to practice in high school or college. They do, however, excel at text-messaging and similar brief format activities. How might you use cell phones’ texting capacities, for example, in your exhibition space? Once you have Millennials contributing as individuals, you can adapt your content to move them up Nina Simon’s hierarchy of social participation.

UPDATE: Since I wrote this post, NPR has posted another segment in their Museums in the 21st Century series–and this one addresses how the culture of testing has impacted field trips for school kids.

Percolations: Museums and Social Networking Sites, Part V

Note: This is part V of a series. Read part I, part II, part III, and part IV.

All right. . . Now that we’ve taken a whirlwind tour of some of the web’s most popular social networking sites, let’s take a moment, sit back, and enjoy a cup of a favorite beverage. (In the 100+ degree heat we’ve been experiencing here lately, I assure you that for me, it’s not coffee.) Let’s pretend I’m a good hostess and for those of you in cooler climes, I’ve put on a pot of coffee to, well, percolate.

As I said in part I of this series, museums’ participation in social networking sites should allow museum content to percolate, to recirculate and gain flavor as that content is passed among Internet users and, we hope, among visitors to museums, who then return to the Web to post their thoughts–and thus museum content persists. Which of the sites I’ve discussed are most successful in allowing for percolation?

1. Flickr: Flickr is a flexible site who usefulness to museums is limited only by museum professionals’ imagination. Best of all, museums’ Flickr projects may be driven by users rather than by museum staff.

2. Twitter: Twitter is labor-intensive in that it requires staff to post frequent “tweets.” But it doesn’t take a lot of staff time, and there’s no learning curve to speak of. And if you did take the time to plan out a marketing campaign, Twitter would allow for a good deal of creativity–and keep your institution in front of Twitter users. Imagine, for example, the tweets of a charismatic and quirky (or, even better, well-recognized) historical figure. Robert E. Lee posts from Gettysburg. Harriet Tubman from the Underground Railroad. (Who wouldn’t add Harriet Tubman as a friend?) The folks at Plimoth Plantation share their daily trials and joys, all in their particular dialect.

3. YouTube: YouTube is fun, and used properly–for contests, to hype exhibits, to add extend exhibit content and concepts–it could be a useful tool. Look around to see what other museums are doing–and then call their marketing departments to gauge their understanding of their YouTube campaigns’ success–before you invest in the hardware and staff training (or expensive video consultants’ fees) necessary to produce quality serialized video.

4. MySpace: Edgier than Facebook, MySpace can give museums an online presence among a younger crowd. But it’s not clear to me how MySpace will keep your institution’s name regularly in front of MySpace users.

5. Facebook: Facebook is a good way to connect with existing communities–for example, to pull together a group of docents–but it’s probably not the place where your museum is going to take off among the younger set.

6. LinkedIn: Little percolation here, but lots of possibility for back-room dealings among donors and muckety-mucks who, used strategically, might raise the profile of your museum. I’d use LinkedIn to open a dialogue with key players in museum- or technology-related fields.

So. . . the salon is open in the comments. What are your thoughts?

Additional Resources

There’s a ton of good writing and thinking out there about museums and the social web, including social teworking sites and mashups. Here are a few that deserve further mention, along with some quotes from each article or post.

There’s an International Museum Professionals group on Facebook. (h/t: fresh + new)

electronic museum’s thoughts on Facebook:

So….should museums be on Facebook? Yes, probably, if that presence does something interesting and motivating for users. Should museums be on Facebook just because it’s there? Obviously not.

Via the above post at electronic museum, we learned about a discussion on Facebook on the Museums and Computer Network listserv. Here’s an excerpt from a posting by Mike Ellis:

Maybe museums would be better off developing some simple Facebook apps –

for example to let users search (and use) their images. See Photobubbles

as one simple idea (http://apps.facebook.com/photobubbles) – if you let

users add captions and bubbles to a selection of images from your

collection you’d be immediately capturing a young and viral audience.Just creating a group “Museum of ****” probably wouldn’t cut it, except

with the same old audience you already had, or people you already work

with…

At roots.lab, there’s an excellent post that claims to be “Social Web 101 for Nonprofits, Or, How the ‘Live’ Read/Write Web Can Help Your Organization Achieve Amazing Things.” An excerpt:

The social web is about:expressing identity. The social web allows individuals to share aspects of their lives with friends, family, or anyone at all, via easy-to-use online tools. It allows people, whatever their motives — and the motives of a MySpacer, a business blogger, a “wikipedian” and so forth are surely very different — to reveal a tangible sense of who they are and what they’re interested in.

relationships and trust. The social web makes it easy to find and start talking with others who share your interests, whose ideas you like, who make pictures, videos, writings that you find appealing. Enjoy a few positive interactions with this sympatico person you’ve found, and trust will begin to ensue. People develop authentic bonds with others through the social web.

user-driven websites. The social web makes the little guy important — anyone can post videos to YouTube, engage in back-and-forth with the authors of widely read blogs, or help write and monitor wikipedia. It also makes the online behavior of the little guy important — each click matters, when giving the thumbs-up to an article on Digg, watching YouTube videos, or even using Google, and figures into these sites’ ranking of content. The social web allows users to be active, empowered participants in the production and distribution of media, the word-of-mouth reputation of a business, the grassroots support for a political candidate, and other tides that course through our culture.

From ProjectsETC, information on user-generated content and cultural activity:

Allowing users to generate their own content can also benefit those with different social, cultural and digital experience or expectations. With hard-to-reach groups, learning how to use these resources can be as important as the end result. At a time when museums and galleries are challenged to demonstrate their social relevance and inclusiveness, such content can be particularly helpful.

Ideum posts on Flickr mashups and interestingness and Mashup of the day and other thoughts.

At Past Thinking, news of Historyscape, a heritage mashup.

At 24 Hour Museum, a post by Nick Poole, “Are Museums Doing it Right?” An excerpt:

The first market for museum websites is the direct user community. These are the people who regularly visit both museums and museum websites, and who make use of their online databases to carry out detailed research into the objects in their collections.The second, much larger group, is the indirect community of millions upon millions of people for whom the Internet is both an information resource and a kind of hyper-connected valet, able to cater to their whims, needs and wishes 24 hours a day.

So far, the majority of our services have been targeted at the former. But who are these people? Do they really exist outside a small number of academic research institutions? Ask the majority of people about the information they want from a museum and they are likely to want to know things like where it is, when it’s open, and whether there’s somewhere for them to have a picnic with the kids. So why is it that we have spent so much time and effort delivering complex searchable databases of catalogue records?

As always, feel free to share your own links to resources in the comments.

(Original percolator-lamp photo by Gary A. K., and used under a Creative Commons license)

Percolations: Museums and Social Networking Sites, Part III

Note: This is part III in a series. Read part I and part II.

Flickr

When it comes to museums and social networking, Flickr is where the action is and should continue to be. Unlike Facebook and MySpace, where visitors can leave notes or comments, Flickr allows people to actively create the core content in what Flickr calls a “photostream” or “set.” And besides, people like pictures! Some people may feel intimidated by new media terms like blogs, Facebook, and MySpace (as well as our attempts to define them), but “photo sharing” is, in the industrialized world at least, just about universally understandable.

To say museumfolk have been thinking about Flickr is an understatement. We’re crazy about it, it seems, and there’s a ton of good writing about using Flickr. Accordingly, I’m going to create a handy-dandy link list here, and you can visit those articles and Flickr pages that most interest you, ‘K?

Meditations on Flickr

Bath Kanter reported in March 2007 about some recent projects by museums in Flickr.

Francesca of Making Conversation with Museums reports on Tate’s use of Flickr. You can read more about the How We Are Now: Photographing Britain project at the Tate’s website.

Nina Simon of Museum 2.0 gives us five reasons museums should use Flickr.

Jim Spadaccini writes about Flickr mashups as well as about one of Ideum’s Flickr-based projects.

Musematic asks whether museums might use Flickr to track potential donors’ collecting habits and points us to an article at Evil Mad Science Laboratories on organizing a collection in Flickr.

Random Connections reflects on the Pickens County Library System’s use of Flickr.

Stephen Downes wants to create a Canadian Art photostream on Flickr, but has been stymied by museums’ photography policies on regarding works in the public domain. e-artcasting reflects on a similar issue.

Ruth Graham writes at the New York Sun about museum visitors’ surreptitious snapshots, some of which end up on Flickr.

Museum projects on Flickr

You can find a ton of museum photo groups, some initiated by museums but most not, by doing a search for “museum” in Flickr groups.

East Lothian Museum shares artifacts on Flickr. An example:

Fisher girl’s costume from the East Lothian Museum collection on Flickr, used under a Creative Commons license.

The Brooklyn Museum has a Flickr page with a lot of public groups.

The Walker Art Center also has a number of photo sets as well as two groups.

Stajichlog alerts us to theMoMAProject[NYC] on Flickr. It’s a group photo pool with more than 17,000 photos.

National Museums Liverpool asked photographers to post photos to Flickr that replicate photos in the museum’s collection of Stewart Bale photographs.

Special mention needs to be made of e-artcasting, which is increasingly becoming a hotspot for discussions of, and projects related to, sociable technologies in museums. Their most recent project is Museums in Libya, in which lamusediffuse has harnessed Flickr users to create a map of museums in Libya, complete with photos. Other e-artcasting projects include the e-artcasting Flickr page, the e-artcasting Listible page, the e-artcasting wiki, and the e-artcasting del.icio.us page.

On to part IV. . . YouTube, Twitter, and LinkedIn.