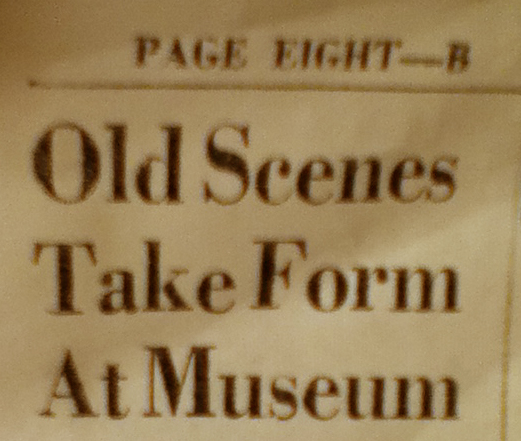

While researching local history, one of my students recently came across an old newspaper article she thought I’d find amusing. Titled “Old Scenes Take Form At Museum,” it was a piece on a new exhibit opening in the state history museum.

I do indeed find museum history interesting, so I was eager to see how the exhibit was described, what motivated the museum to put it up, and to compare it with the exhibits in the museum today so that I can get a better sense of how the museum’s exhibition philosophies and priorities have shifted.

You can see where this is going, right?

The exhibit featured in the newspaper is still up today, and from the description in the article, it appears it hasn’t changed at all.

The newspaper article was published in the early 1960s.

A cautionary tale

My point in writing this post is not to shame or embarrass the museum in question. (It certainly isn’t alone in having permanent exhibits that are, well, permanent.) As with many state history programs—and, I’m guessing, like many such programs in politically conservative states, where education tends not to be funded as fully as it might be elsewhere—it’s clear even to the casual visitor that the museum doesn’t have the money to mount new exhibits on a regular basis.

Still, it’s important to point out the liabilities of such an approach to exhibitions to underscore the importance of keeping up-to-date with museum theory and practice.

Visitors

First, it’s not good when visitors say about your museum—as did the students, aged 20-50, I took to this museum last month—”It hasn’t changed since I was a kid.” The number of visitors who appreciate the nostalgia factor is likely to be far smaller than those who would like to see a new exhibit. Late last year, Reach Advisors delved into their databases to determine what visitors’ attitudes are to changing exhibits—and whether these attitudes differ among museum members, frequent visitors, and occasional visitors. Among their findings:

- Museum visitors appreciate changing exhibits.

- Museum visitors who expect more change in exhibits but don’t see that change happening are less likely to be satisfied with a museum.

- “Children’s museums, art museums, and more traditional history museums should still take heed of the demand for changing exhibitions.”

- “Museums of any type that are specifically seeking to attract family audiences should also bear in mind how important change is to parents.”

Changing exhibitions does not necessarily mean huge costs, though costs are certainly a factor. Of the written-in comments we examined asking for more changing exhibitions, none referred to what we call “blockbuster” exhibitions. Some suggested small changes to liven things up. Change might be a “science in the news” area, which changes on a weekly basis but would not necessarily meet design standards for a longer-lasting exhibition. Change can be delving into the permanent collection and highlighting an artist, or a local history topic, and featuring those items through a new lens (a tactic deployed by many museums during these rough economic times). Change doesn’t mean an expensive line item, and it doesn’t mean changing over the entire museum every six weeks, though it does mean a commitment of some funds and considerable time.

Funding agencies and foundations

One of the most commonly asked questions on humanities and arts grant applications today seems to be some variation of, “What’s innovative about your project?” A museum might be able to find a grant writer who could answer that question relatively persuasively about a proposed exhibition redevelopment, but if I were on a grant proposal review committee—and I have been—I would be looking for evidence that the museum has dabbled in whatever brand of innovation its staff wishes to implement. In the case of this particular museum, if I saw that most of the exhibits were 30, 40, or 50 years old, I would wonder about the museum’s capacity to implement best practices in museum education and exhibition—simply because I don’t see many signs in the current exhibits that the museum is even interested in experimenting with, say, interactivity or with exhibit panels of fewer than 300 to 500 words.

Let’s say this museum knows it should implement a new degree of interactivity but it hasn’t. Because authentic artifacts are the traditional history museum’s stock-in-trade, incorporating interactivity may at first seem a challenge because visitors can’t touch the artifacts the way they can interact with objects and manipulatives in a science center or children’s museum. Furthermore, if the exhibition development and education staff of a history museum hasn’t been provided quality opportunities for professional development—and I don’t know if that’s the case with this particular museum, but the museum’s exhibits do not reflect the at least last 20 years or so of theory and practice—then they might not be able to think beyond expensive replicas and the sometimes complex “recipes” for fabrication designed by science centers like the Exploratorium. Once we can force ourselves to think beyond video kiosks, replicas, and dynamic science interactives, we find many possible baby steps toward interactivity or visitor participation. It’s easy to add a simple paper-and-pen or token-based polling system for visitors, create laminated cards or brochures that offer alternative tours through the museum based on individual visitors’ interests, or affix QR codes to exhibit labels to direct visitors to more in-depth content on the museum’s website or to additional photographs of the object from angles that aren’t visible to the visitor.

Interactivity can be simple and inexpensive to integrate into an exhibit, and much information is available freely online about how to successfully include interactive components in an exhibit. There’s no longer any good reason a museum hasn’t adopted such techniques, and it doesn’t make sense for a museum to ask for funding for a new, innovatively interactive exhibition if it hasn’t shown interest or capacity in more basic interactive techniques.

Donors

Although museum professionals know that in most museums only a small percentage of artifacts ever see the exhibition floor, my sense is that few donors to local history museums understand their treasures likely will remain in storage in perpetuity. Donors who wish to see their gifts on display during their lifetimes may be dissuaded by decades-old exhibits or by temporary exhibits not drawn from the museum’s collection. In addition, speaking for myself, I’d be unlikely to donate my family’s beloved heirlooms to a museum if the institution lacked the creativity and wherewithal to interpret artifacts in ways that challenge visitors to think critically and creatively.

Solutions

Let’s consider a few ways to update this exhibit relatively inexpensively and thus gain some respect in the eyes of visitors, current and prospective donors, and even funders.

A wringer washer in Wyoming. Image by arbyreed, and used under a Creative Commons license.

First, a description. The “old scenes” mentioned in the newspaper article comprise a kitchen and porch exhibit whose central feature appears to be laundry. I haven’t paid attention to the exhibit lately, but if memory serves, there is a wringer washer, soap containers, and some other household goods arrayed on a porch. The article describes it thus: “The porch display. . .will include an old hand-crank clothes washer, ice-box refrigerator, rocking chairs and a stack of wood.”

The exhibit depicts, in other words, a tiny slice of domestic life at the turn of the last century. My reading of it is as cute and nostalgic in a way that makes me uneasy because the woman who would be using the objects displayed in the kitchen and on the porch is absent; her labor becomes invisible. So, in this scenario, let’s find a way to make that woman and her labor visible to the visitor.

Assuming visitors can get network reception inside the museum’s building, I recommend adding multimedia content accessible via smartphone, 3G or 4G tablet, or, if the museum is equipped with public wifi, a wireless device like an iPod Touch or wifi iPad. Having such content available on devices a visitor brings with her, or even on a device that can be checked out from the front desk, means that the museum won’t need to buy, maintain, and update a bulky and expensive audio or video kiosk. This content might be accessible through a QR code or simply a URL printed at the bottom of the exhibit’s interpretive panel.

Audio content might include the voice of a woman talking about how tired she is after using all these devices or telling a story about how her curious toddler stuck his hand into the wringer when her attention was directed toward another one of her children, and she cranked the handle (audio of child screaming or crying), and the doctor had to be called to examine the child’s hand. Alternately, the printed URL might take the user to a YouTube video of someone using a hand-cranked washer:

In an underfunded museum such as this one, audio content could be created by interns who undertake research into the use of such machines, then are given free range with Audacity or another free or low-cost audio editing program. Interns also could seek out such video footage of an antique washer, such as I’ve posted above, and embed it onto mobile-friendly pages on the museum’s website. (Of course, best practice for any institution would be to include a link to a transcript of the audio for deaf visitors and a description of the video for blind visitors.)

Or we could tell a different kind of story. This is, after all, a museum with a quarter million objects in its collection, so it has plenty of artifacts it could be exhibiting. Perhaps we see the open porch at a moment of transition; it’s being enclosed to make a laundry room, and the woman has set her old hand-cranked washer and wringer out in the yard to make way for her new machine, which features an electric agitator. Audio or textual content could describe the woman’s feelings about the new machine at the moment of its arrival, as well as showcase her ambivalence a few months down the road, when she complains about constantly having to repair it, or when she expresses the belief that it’s too rough on her family’s clothes, wearing them out prematurely.

In this scenario, collections and education staff could establish a schedule whereby the laundry machines and interpretive content (text or audio) are updated every few months. Visitors could play a game, made with magnets and laminated photos of old laundry machines, in which they try to place the laundry machines in the correct chronological order.

Or, of course, we could abandon laundry altogether. It isn’t, after all, the sexiest subject. Moving away from laundry, however, doesn’t have to mean a complete (and costly) exhibit renovation. The relative openness of the porch exhibit “stage” lends itself to any number of scenes in a way that, say, the built-in cabinets and framed windows of the restored formal dining room in an adjacent exhibit do not. The museum could tell any number of stories about race, class, age, gender, leisure, and labor.

And need I mention that it’s best practice to rotate artifacts? Changing exhibits allow objects relief from light, vibration, and other damaging phenomena.

Share your thoughts in the comments

I’d love to hear your own stories of

- permanent exhibits that became a little too permanent, and how the museum resolved the issue;

- low-cost changing exhibits;

- inexpensive ways to add or integrate simple multimedia content that enriches an exhibit or shifts its meaning; and

- old exhibits updated to become more interactive or participatory.

I’m also eager to hear what solutions you’d propose to the particular challenge I’ve shared in this post. What advice would you give the museum staff?

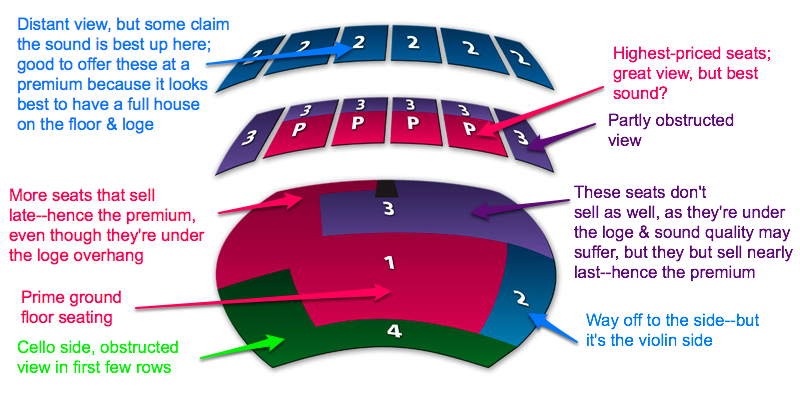

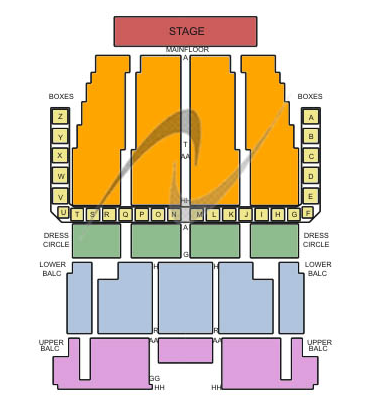

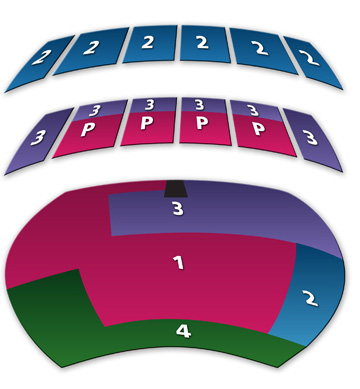

In consultation with some arts marketing gurus—and I’m afraid the name of the firm is escaping me right now, so please comment if you know the name of the consultants who helped redraw the floor map—the Symphony completely changed its subscription price points. Some people’s annual subscription prices increased dramatically, while others’ plummeted by hundreds of dollars. The map looks kind of crazy at first glance:

In consultation with some arts marketing gurus—and I’m afraid the name of the firm is escaping me right now, so please comment if you know the name of the consultants who helped redraw the floor map—the Symphony completely changed its subscription price points. Some people’s annual subscription prices increased dramatically, while others’ plummeted by hundreds of dollars. The map looks kind of crazy at first glance: Some of those Level 4 seats are pretty prime. Imagine being in row 6 or 7, at the inner edge of the green area. Yet those are the cheapest seats in the house–currently only $79 for a season subscription to six classical music concerts. (And yeah, you can bet my parents now have a couple of those seats.)

Some of those Level 4 seats are pretty prime. Imagine being in row 6 or 7, at the inner edge of the green area. Yet those are the cheapest seats in the house–currently only $79 for a season subscription to six classical music concerts. (And yeah, you can bet my parents now have a couple of those seats.)