I’ve become quite enchanted lately with the tweets of many of the museums and related institutions I follow on Twitter. I’m a sucker for a link to a picture or video of a baby animal, even if it is an amorphous little shark pup. That said, I’ve noted some carelessness lately in the way institutions tell stories about their animals. Check out this video, for example, from the Georgia Aquarium:

Issues of animal transportation, care, and trauma aside–and I do believe aquaria on par with the Georgia Aquarium adhere to best practices in this regard–moving this one animal has expended a tremendous amount of energy. The manta ray’s carbon footprint went from zero to who knows how large.

Zoos and aquaria have two primary narratives: “We bring the world’s animals to you” and “We bring the animals here to study and save them.” Yet as visitors to these institutions finally begin to catch on to the whole giant carbon footprint = climate change = harm to animals and their environments equation, zoos and aquaria are going to have to learn to either counter narratives of wasteful transportation (a dangerous travelogue) or limit their acquisitions to local and regional species. Although the Georgia Aquarium is a spectacular institution that features local species as well as animals from around the world, I must admit I’m more sympathetic to aquaria, such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium or the Long Beach Aquarium of the Pacific, that focus on the bodies of water on which they sit, even if they be (as in the case of Long Beach) especially large ones.

“But Leslie,” you say, “the Georgia Aquarium is being transparent in celebrating its ingenuity in bringing this ray to the public. Can’t you let them tell this one story?”

Sure, one story. But then there’s this:

Same kind of story, only with a less charismatic animal and not quite such spectacular technology. I’m sure if I searched I’d find plenty of other dangerous travelogues from zoos and aquaria.

For decades zoos have been tweaking the enclosures of the animals they have on display in the hopes, among other goals, of reducing stereotypies and other unhealthy behaviors. As zoos increasingly move elephants off display because zoo environments are antithetical to elephants’ good health, thoughtful people are going to wonder if whale sharks and beluga whales really do belong in relatively small tanks (as they already wonder about displaying dolphins), what kinds of energy go into supporting them, and in what ways we’re damaging not only the animals but the environment. (Kudos, by the way, to the Cal Academy’s Steinhart Aquarium for eschewing the “crystal clear” industry standard of aquarium water in favor of a more energy efficient system that uses less electricity and water because it requires less filtering.)

These dangerous travelogues remind me of a Sea World phenomenon Susan Davis highlights in her book Spectacular Nature:

[W]ith few exceptions complexity, local connections, and controversy are missing. Sea World’s environmental messages are little different from the flat morality play of the rest of corporate environmentalism in their emphasis on individual responsibility for cleaning up litter. (150)

I don’t mean to equate our nation’s best aquaria with Sea World, but there are parallels in that the aquaria are sending mixed messages when they roll out these dangerous travelogues–by which I mean narratives and actions that are dangerous for the environment and dangerous for public relations. And it’s not just travelogues about animals coming to the aquaria that are problematic–it’s also the stories these institutions (don’t) tell about the impact of human travel (daily or otherwise) on the earth.

At the Monterey Bay Aquarium and, I’m sure, at other aquaria, visitors can pick up wallet-sized cards that help them decide whether to buy, for example, wild or farm-raised salmon. I’ve seen elsewhere cautions that people need to cut up the plastic loops that hold together six packs of soda or beer. While these certainly are steps individuals can take, they do not challenge the complicity of larger entities–nations or corporations–in the threats human activities pose to ocean life.

This brings us, of course, to corporate sponsors. When the New England Aquarium receives donations from energy companies or the World Aquarium in St. Louis accepts donations from automobile, beverage, and pharmaceutical corporations whose industries may be polluting the earth and its waters, those relationships should be made transparent. What are aquarium visitors not hearing about pharmaceuticals in our waters and the ways they threaten freshwater and marine species?

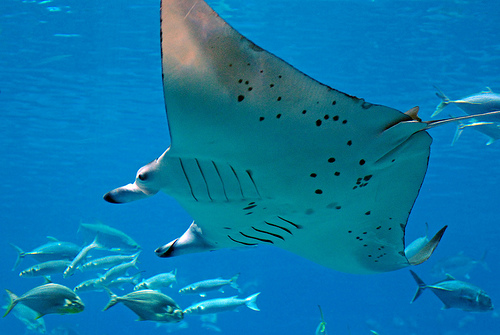

Photo of Georgia Aquarium’s manta ray by Tim Lindenbaum, and used under a Creative Commons license.

It’s nice to provide visitors with cards about which fish to eat or not eat, or postcards they can mail directly from an institution asking their local representatives to vote for a bill to form, say, a marine preserve or to fund more marine research. But at the same time, aquaria need to be telling visitors that they can do more–much more–but that doing so requires collective rather than merely individual action. Aquaria and zoos and natural history museums must learn to better harness the thoughtfulness and excitement of the one percent of visitors about which Nina Simon wrote yesterday.

And putting videos on YouTube of manta rays being flown across the country? That’s not the way to engage that one percent; it raises their hackles rather than their enthusiasm.