Although I teach in a museum studies graduate program (and wish I could do it full-time), my primary job is to help faculty become more thoughtful about teaching undergraduates at the University of California, Davis. Since I began working in the university’s Teaching Resources Center, faculty have come to me for assistance with myriad issues, but there are three that arise more frequently than others:

- They are teaching very large (200-900 student) classes.

- They feel compelled to cover large amounts of material.

- Their students can’t think analytically–or write.

The first and third of these quandaries are generational ones in that in the U.S. we are educating students in an era of reduced resources, higher enrollments, and high-stakes testing in K-12. The second quandary relates intimately to the first and third.

The problem of coverage, what I have heard termed “the tyranny of content,” has of course long plagued curators and exhibition developers as well as professors. In museums it takes many forms: a desire to exhibit all the varieties of one object (e.g. butter churns, to borrow an example from Dan Spock) or to cover an immense amount of material and history in too small a hall (e.g. the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s African Voices exhibition), for example.

Museums have also long had to deal with large numbers–sometimes crushing numbers–of visitors to new, blockbuster, or otherwise favored exhibitions. How to serve so many people while still giving each visitor a sense that she has had a personalized interaction with the museum content is one of the great quandaries of museum education, and we’re barely scratching the surface of this problem with some tentative experimentation with digital and/or mobile devices.

The new generation of young adults, however, presents a particular challenge to museum educators, exhibition developers, and docents. If they attended a public university in the U.S., and especially in California, these “Gen Y” “Millennials” are likely to have been a victim of what I call the factory farming of students: large lecture halls crammed with students, multiple-choice tests, and a long series of general education courses that represent to them not opportunities to explore new disciplines, but rather a series of boxes to be checked off: the writing requirement, the diversity requirement, the quantitative thinking requirement, etc. In addition, these college students and graduates came of age under No Child Left Behind, a regime of high-stakes testing that led school districts to “teach to the test” rather than engage in the student-centered learning that imbues young people with curiosity, gives them the intellectual tools and cultural literacy they need for interpreting and analyzing the world, and ensures a desire for lifelong learning. Many of these young people are thus victims of large-scale, depersonalized educational systems. Trained to memorize and regurgitate instead of interpret and create, they are not equipped to engage with museum content–and worse, they may not even be aware of their predicament.

Clearly, this generation provides an opportunity for–or, rather, is in desperate need of–visitor studies that examine how trends in our K-12 and university systems affect museumgoers’ understanding of material culture, art, hands-on science exhibits, and natural history objects. What new kinds of interpretation will we need to develop? How can we teach interpretive skills to those in galleries as well as convey content?

Based on my own experiences in the Gen Y classroom, my observation of others’ classes, and my consultations with faculty, I offer here some tentative suggestions for meeting the needs of Gen Y learners in the museum.

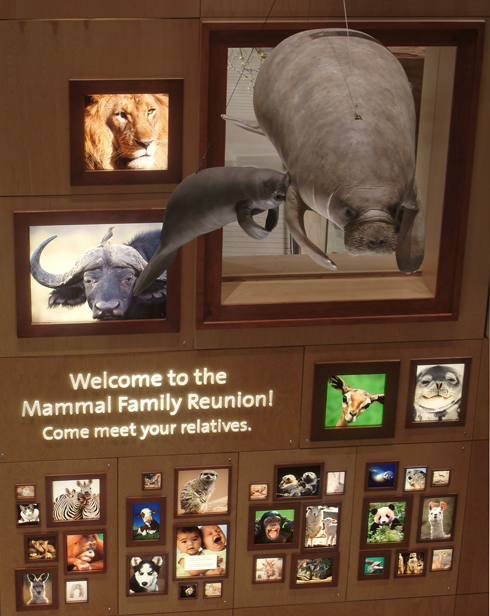

Provide strong orientation. By this I mean museums need to strike a balance between free-choice learning and making learning objectives painfully explicit. How this might look will vary by institution, but one place to start is with a strong framing device. One exhibition that accomplishes this well is the new mammal hall at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. There is no clear pathway through the exhibit hall, and it’s easy for the dramatically lit trophy-quality mounts and evocative soundtrack to overwhelm the visitor with their pure spectacle. However, the museum has framed the exhibition in an orientation gallery, using this conceit:

photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

Visitors are welcomed to the Mammal Family Reunion and learn that mammals can be identified because they all share three basic traits: they have hair or fur, they possess specialized middle ear bones, and they produce milk for their young. Elsewhere in the exhibition, visitors learn more about mammals’ diverse environmental niches and adaptations, but the framing device is that all of these animals, despite their tremendous diversity, are from the same “family” (more precisely, the same class within the phylum chordata). Certainly there are some of you saying, “Really? That’s all people are going to take away from this exhibit? That mammals are hairy, produce milk, and have something in their ears?” To which I say:

- Millennials have learned to memorize and retain, at least temporarily, facts about a subject. Learning (or, in the case of college-educated millennials, re-learning) three things about mammals is an excellent starting point for them.

- Millennials’ science education has suffered in K-12 as a result of NCLB’s emphasis on math and reading comprehension. Drop them in a place as large as the NMNH and they’re going to feel overwhelmed. Give them a flash card’s worth of information to begin with, and they’ll feel comfortable.

- This is only orientation information, a short list of objectives they can carry with them as they wander around the exhibition and apply these facts or principles to what they’re seeing.

Ideally, as the visitor walks through the mammal hall, she would be learning concepts that build upon these basics. For example, mammals all have fur or hair, but they have differing amounts of it. A jackrabbit and a sea otter have dramatically different densities of fur because they have adapted to living in very different environments. Although they descend from a common ancestor, these animals evolved in ways that allowed them to occupy, and even thrive in, a niche.

Help visitors develop analytical frameworks and interpretive skills. We see a bit of this in the example above. Visitors learn three basic facts, and then begin to make observations on their own about each fact–e.g. that mammals’ fur density differs by species. Next the visitor should be prompted to puzzle through why the fur differs. And then comes the big lesson: What are humans doing to change the environments in which these animals live? What happens when an animal evolves over tens or hundreds of thousands of years to occupy a niche that is decimated by humans in a matter of years? What are humans’ responsibilities to endangered mammals? Why might humans be more amenable to protecting mammals (AKA “charismatic megafauna”) than they are other species, and what are the advantages and liabilities of this approach to conservation? Labels, podcasts, hands-on activities, docents/explainers, and visual organizers all can contribute to this learning.

Customize streams of content. Provide interpretive tours organized around visitor interests instead of gallery space. Offer audio tours created by a variety of experts or amateur enthusiasts, including “guerrilla” audio tours. Examples from our mammal hall might be an evolution-focused podcast, a conservation-focused activity book or handout for children, or ways for visitors to send themselves the URLs of content related to the exhibition areas in which they’re most interested–e.g. polar mammals or desert creatures.

Provide content in multiple formats. The streams of content you provide must be accessible in several formats. This might mean visitors can generate e-mail messages to themselves–perhaps a series of autoresponders–to learn more post-visit, send to their mobile phone or PDA the snippets of code they need to embed customized media in their blogs or Facebook news streams, or pick up topic-specific paper handouts upon exiting the exhibition.

Offer opportunities for collaboration. Hands-on exhibitions sometimes call for cooperation among visitors, but opportunities for collaboration are rare–and it is a skill that Millennials may not have had the occasion to practice in high school or college. They do, however, excel at text-messaging and similar brief format activities. How might you use cell phones’ texting capacities, for example, in your exhibition space? Once you have Millennials contributing as individuals, you can adapt your content to move them up Nina Simon’s hierarchy of social participation.

UPDATE: Since I wrote this post, NPR has posted another segment in their Museums in the 21st Century series–and this one addresses how the culture of testing has impacted field trips for school kids.