In collaboration with its various partners, the New Media Consortium (NMC) each year publishes three versions of its Horizon Report: one each for K-12 education, higher education, and museum education and interpretation. Each publication forecasts trends in technology in these respective sectors.

The reports always generate thoughtful discussion among practitioners in these fields, and I’ve noticed that of particular interest to many folks are the technologies forecast to be three to five years out. That said, I haven’t heard much conversation within each field about the others’ reports. This is an odd gap in the discourse about technology, as formal and informal education influence one another in dynamic ways. With mobile devices becoming increasingly ubiquitous across socioeconomic classes, the lines between informal and formal educational spaces are blurred, sometimes beyond recognition or restoration.

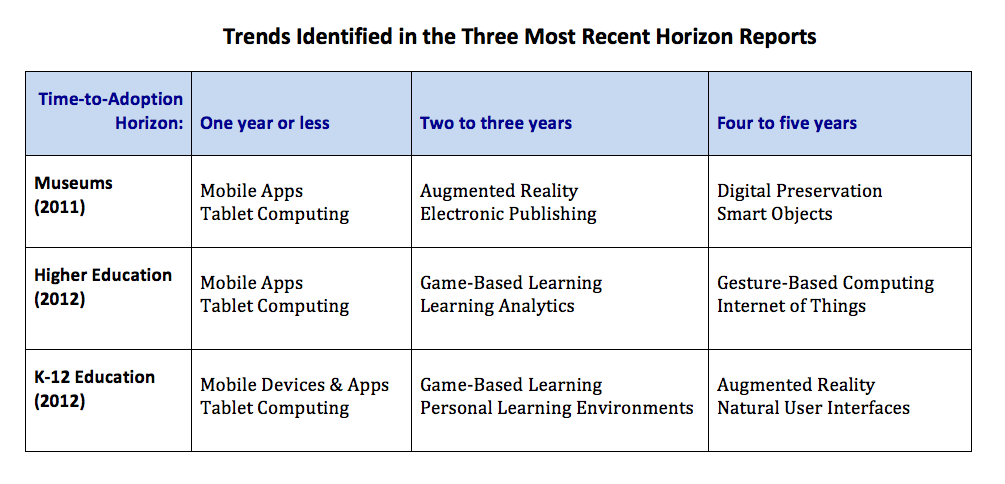

I’ve created a table comparing the most recent NMC technological forecasts for museums, higher ed, and K-12 education. Take a look:

Click image to enlarge. Note: I received a pre-release copy of the 2012 K-12 Horizon Report. It’s not yet available in its entirety to the public,but those of us with pre-release copies are encouraged to write about it.

Click image to enlarge. Note: I received a pre-release copy of the 2012 K-12 Horizon Report. It’s not yet available in its entirety to the public,but those of us with pre-release copies are encouraged to write about it.

I don’t think it’s a surprise to anyone within these educational sectors that mobile apps and tablet computing are arriving on the scene. Students, faculty, museum visitors, and museum staff frequently carry smart phones that allow them to access all kinds of information at a moment’s notice. Nor do I think it’s particularly surprising to suggest game-based learning and PLEs are hot in K-12, or that games and learning analytics are going to take off in colleges and universities. However, the rest of the technologies on this chart are, while certainly not controversial, more open to debate and speculation.

I’d like to take some time, then, to reflect on the relationships among technologies such as augmented reality, games, analytics, PLEs, digital preservation, smart objects, and gesture-based computing, and consider how students’ and visitors’ use of these technologies might be brought to bear within museum exhibitions, programming, and digital outreach.

I’ll be publishing a series of posts on the utility of, and the possibilities inherent in, these technologies—taken individually, and as a constellation—across sectors.

Definitions

But first, some definitions, pulled directly from the reports:

Augmented reality is “the layering of information over 3D space” to produce “a new experience of the world,” a “blended reality” (Museums, p. 18).

Game-based learning encompasses a broad spectrum of “serious play,” including “games that are goal-oriented; social game environments; non-digital games that are easy to construct and play; games developed expressly for education; and commercial games that lend themselves to refining team and group skills. Role-playing, collaborative problem solving, and other forms of simulated experiences are recognized for having broad applicability across a wide range of disciplines” (Higher Ed, p. 18).

“Learning analytics refers to the interpretation of a wide range of data produced by and gathered on behalf of students in order to assess academic progress, predict future performance, and spot potential issues” (Higher Ed, p. 22).

Personal learning environments (PLEs) cross the borders between formal and informal education in their support of “self-directed and group-based learning, designed around each user’s goals, with great capacity for flexibility and customization. The term has. . .crystallized around the personal collections of tools and resources a person assembles to support their own learning” (K-12, p. 24).

“Digital preservation refers to the conservation of important objects, artifacts, and documents that exist in digital form.” Software and hardware can become obsolete very quickly, and museums that collect electronic media are going to find such the management of such artifacts and resources increasingly complex. “Digital preservation calls for a new type of conservationist with skills that span hardware technologies, file structures and formats, storage media, electronic processors and chips, and more, blending the training of an electrical engineer with the skills of an inventor and a computer scientist” (Museums, pp. 26-28).

Gesture-based computing and natural user interfaces allow users to engage in virtual activities with motions and movements similar to what they would use in the real world, manipulating content intuitively” (Higher Ed, p. 27; K-12, p. 33).

“The Internet of Things has become a sort of shorthand for network-aware smart objects that connect the physical world with the world of information. A smart object has four key attributes: it is small, and thus easy to attach to almost anything; it has a unique identifier; it has a small store of data or information; and it has a way to communicate that information to an external device on demand” (Higher Ed, p. 30).

Stay tuned. . .

I expect the first of these posts to be up later this week. I’ll link to each post in the series as they become available.

This is great, thanks!! I always have a hard time telling the difference between what’s a game and what’s augmented reality. Augmented reality makes me think of Ghost Chase or Plz Stay Calm where you’re capturing virtual ghosts or running from virtual zombies but I feel like a good location-based museum game layers information on the space while still using role plays and problem solving. For instance, the classic: Ghost of a Chance- is that augmented reality or would it be considered a game?

Great that you’re looking cross-institutionally at this. I feel like there’s a bit of a divide in the games for change crowd: people who are thinking games for education focus on K-12 while folks thinking more of “games for change” look towards museums and informal education. I wonder if the lines will blur between games and augmented reality as those types of games converge.